"Adults who burn out from living in the city pick up their families and move to towns like this for the slower pace, the quiet. They feel they can raise their younger kids in relative peace and safety. What they fail to recognize is that it's their teenagers who suffer boredom and existential low self-esteem in extreme ways."

I’m a very big fan of Gilbert Hernandez, co-creator of

one of the greatest comic series of all time, Love and Rockets. There is an ethereal quality to his work that is

combined with strong characterization and bold, unapologetic art. His Palomar

stories are a young man’s masterpiece but Beto (as he’s known) has continuously

improved throughout his career. Though I’m most familiar with this Love and Rockets stories, I’ve been

slowly working my way through the rest of his oeuvre. Note that the only reason

I’m doing it slowly is that he’s rather prolific. Thirty years after the first

issue of Love and Rockets Beto

continues to regularly publish comics on an annual basis. Some years, he’s even

got three or more publications if you count his collection of serialized works

and original graphic novels.

I’m a very big fan of Gilbert Hernandez, co-creator of

one of the greatest comic series of all time, Love and Rockets. There is an ethereal quality to his work that is

combined with strong characterization and bold, unapologetic art. His Palomar

stories are a young man’s masterpiece but Beto (as he’s known) has continuously

improved throughout his career. Though I’m most familiar with this Love and Rockets stories, I’ve been

slowly working my way through the rest of his oeuvre. Note that the only reason

I’m doing it slowly is that he’s rather prolific. Thirty years after the first

issue of Love and Rockets Beto

continues to regularly publish comics on an annual basis. Some years, he’s even

got three or more publications if you count his collection of serialized works

and original graphic novels.

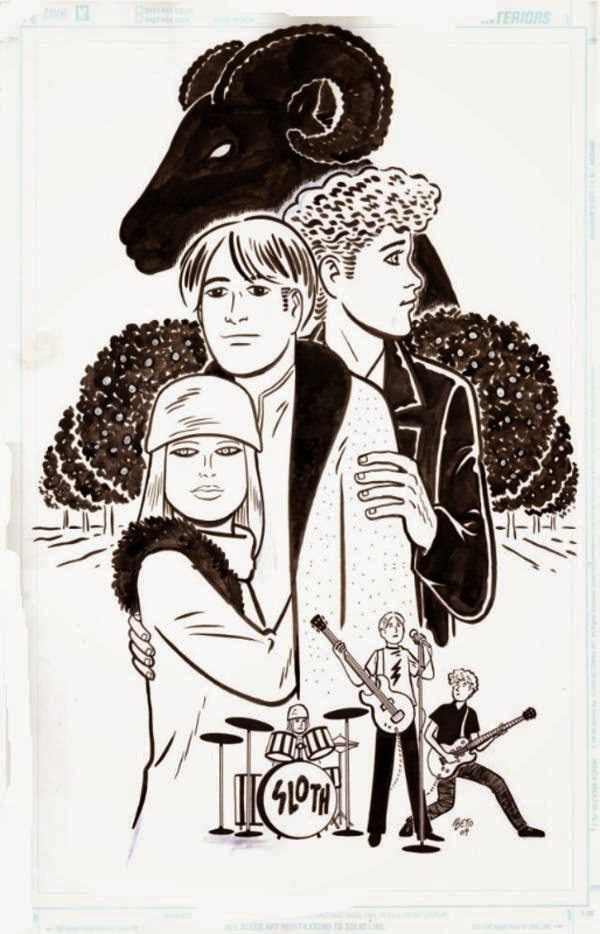

Released in 2006, Sloth

is an original graphic novel. Hernandez wanted to create something that was

different than his Love and Rockets

stories. For those who might not know, Beto’s half of Love and Rockets is a huge, sprawl family epic with dozens of

regular characters who have age in slightly quicker than real-time since their

original appearance. Part of his inspiration for Sloth was to create something with fewer characters and really

focus on them. That’s really what Sloth is.

It’s a study in character and it’s also a study of what it is to be a teenager.

The story is about Miguel, a depressed teen who wanted to

escape reality and willed himself into a coma. The comic starts out with his

reawakening after his year-long coma. We follow him as he re-enters the world

he left behind. Hernandez presents us with a bit of Miguel’s family history and

he also gives us the events that may have led to his coma. Miguel lives with

his grandparents since his father is in prison for selling drugs and his mother

abandoned him when he was a toddler but is now rumoured to be dead and buried

in the lemon orchard, a local haunted spot.

Structurally, Sloth

is fascinating comic. Beto splits the story in two parts, the first dealing

with Miguel’s post-coma return to normal life and he second is Lita’s post-coma

story. The story is linear for the first two thirds (give or take) but the

story is partially rebooted when Lita wakes up. There are interesting parallels

and differentiating storie happening to Miguel and Lita but what really

captivated me was how some parts of the story, those related to Romeo (and

maybe the Goatman?) appear to continue from the first to the second part and

ultimately lead us to a third comatose teen.

Beto has mentioned in an interview (which you can read

here) that the coma is a metaphor for adolescence. In order to understand the

characters you have to understand why they chose to self-induce themselves in a

coma. For Miguel it was a way to escape life. It was too much for him to deal

with but when he woke up, everything was still the same. He still has the same

girlfriend, his band is still together, the legend of the Goatman (who lives in

the lemon orchard and can swap bodies with you using his willpower alone) is

still being circulated. Absolutely nothing has changed and when he slips into

what can only be his final coma, his only regret is that he’s leaving Lita

behind. For Lita, her coma is nothing but an extended dream, a fantasy. Nothing

in her life remained the same. She has different friends, Romeo has become an

incredibly successful rock and roll star. What really makes it a fantasy though

is that everything she wants (a relationship with Miguel, to meet Romeo X, etc)

happen without requiring any real effort. Her post-coma (dream) life is a

fantasy because it depicts an unrealistic portrayal of life where change

happens easily and is always rewarding.

Beto has mentioned in an interview (which you can read

here) that the coma is a metaphor for adolescence. In order to understand the

characters you have to understand why they chose to self-induce themselves in a

coma. For Miguel it was a way to escape life. It was too much for him to deal

with but when he woke up, everything was still the same. He still has the same

girlfriend, his band is still together, the legend of the Goatman (who lives in

the lemon orchard and can swap bodies with you using his willpower alone) is

still being circulated. Absolutely nothing has changed and when he slips into

what can only be his final coma, his only regret is that he’s leaving Lita

behind. For Lita, her coma is nothing but an extended dream, a fantasy. Nothing

in her life remained the same. She has different friends, Romeo has become an

incredibly successful rock and roll star. What really makes it a fantasy though

is that everything she wants (a relationship with Miguel, to meet Romeo X, etc)

happen without requiring any real effort. Her post-coma (dream) life is a

fantasy because it depicts an unrealistic portrayal of life where change

happens easily and is always rewarding.

A big fuss is made over the Goatman but what is his

portion of the story really about? I think the Goatman symbolises change or the

desire to change. Teenagers have their entire life ahead of them and they often

dram of what they will one day be. Few teens actually work towards achieving

any of their goals. Teens are dreamers and because of that they’re static, they

don’t do much. They’re so unmotivated to enact change and better themselves

that they’re rather avoid real life and regress into a cocoon of sleep and hope

everything will fix itself in their absence or that their dreams will come true

all on their own. The problem with this approach is that by the time they wake

up they’ll realize nothing has really changed and their coma approach to life

was counter-intuitive. You can’t just dream of what you want, you have to go

out and obtain it. While Lite and Miguel were busy trying to film the Goatman,

Romeo stayed home and worked on his music. Later, in Lita’s coma fantasy, Romeo

is a successful rock star because he worked hard to achieve his dream. In the

dream Romeo X hangs out with Miguel and Lita and he tells them he’s from the

same hometown as them essentially telling them and the reader that it doesn’t

matter where you’re from, you can achieve greatness if you work hard. I see the

Romeo as being the Goatman and they both represent will power, which Romeo used

to get what he wanted out of life rather than run away from life like Miguel

and Lita did.

Sloth looks and

reads like the typical Beto comic, that is to say all the components are there,

the elliptical storytelling, the heavy-inked bold art and a focus on developing

interesting and deeply flawed characters. It really works though because he

rearranges those components to tell a very effective story about teenagers and

their hopes and dreams. Beto’s later work is often categorized by a false sense

of simplicity. Sloth, despite its

name, is a pretty quick read but unless you slow down and think about what is

happening, you won’t be able to appreciate. My interpretation of the story

isn’t necessarily right and I’m certain there are far more interpretations that

could be made, each of which could be equality validated, but that’s the

pleasure of this kind of comic. Beto doesn’t spoon feed us the answers but he

avoids giving the reader a pile of unrelated visual symbolism. If you focus on

the characters and the recurring elements of coma, dreams, movement and the

Goatman’s famed will power, you can puzzle together a story that sheds light on

the lives of teens and how best to escape it all.

Sloth looks and

reads like the typical Beto comic, that is to say all the components are there,

the elliptical storytelling, the heavy-inked bold art and a focus on developing

interesting and deeply flawed characters. It really works though because he

rearranges those components to tell a very effective story about teenagers and

their hopes and dreams. Beto’s later work is often categorized by a false sense

of simplicity. Sloth, despite its

name, is a pretty quick read but unless you slow down and think about what is

happening, you won’t be able to appreciate. My interpretation of the story

isn’t necessarily right and I’m certain there are far more interpretations that

could be made, each of which could be equality validated, but that’s the

pleasure of this kind of comic. Beto doesn’t spoon feed us the answers but he

avoids giving the reader a pile of unrelated visual symbolism. If you focus on

the characters and the recurring elements of coma, dreams, movement and the

Goatman’s famed will power, you can puzzle together a story that sheds light on

the lives of teens and how best to escape it all.

No comments:

Post a Comment