|

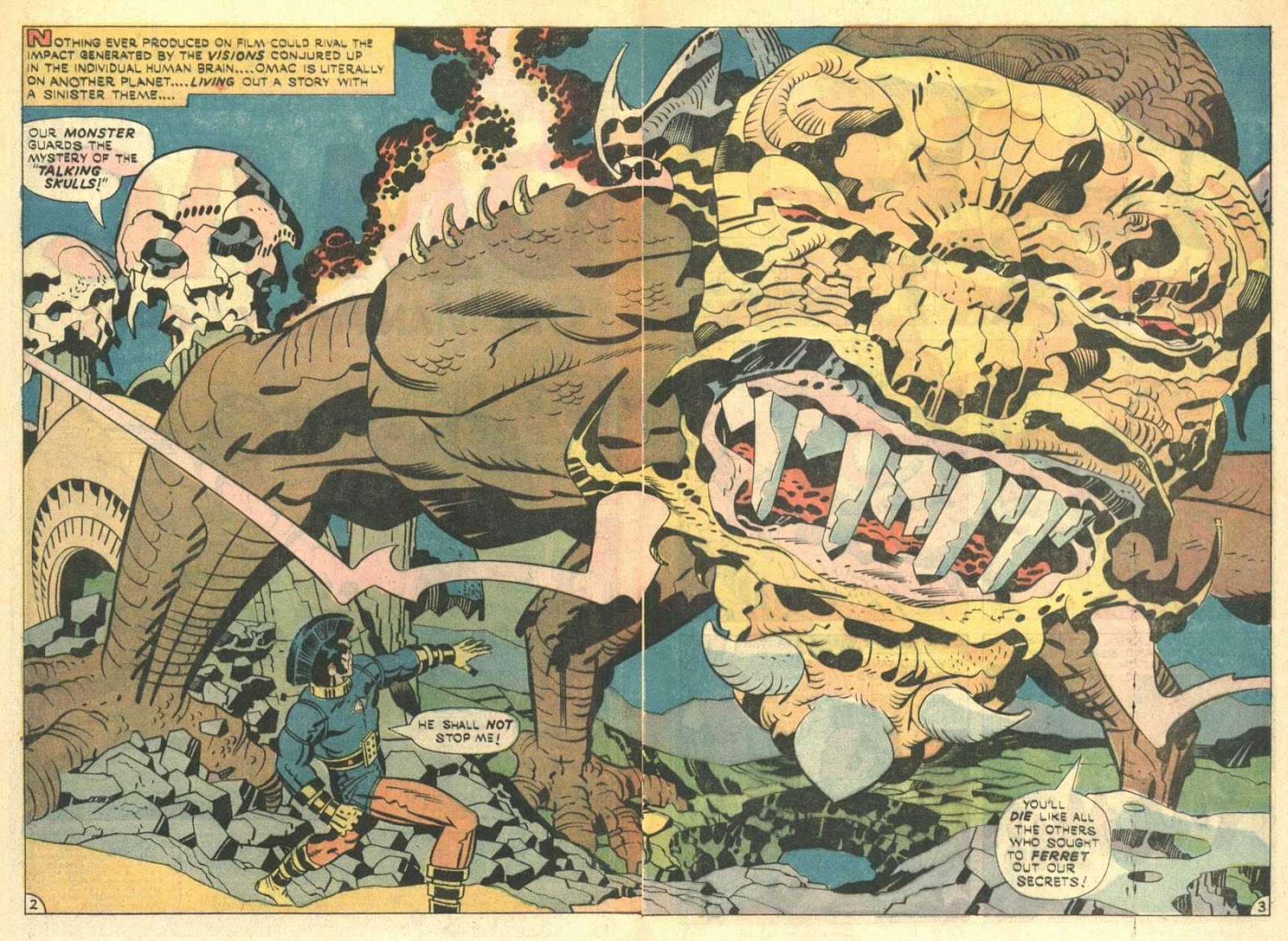

The lame cover of my edition of

Dragonflight. |

Wheel and turn

Or bleed and burn.

Fly between,

Blue and green.

Soar, dive down,

Bronze and brown

Dragonmen must fly

When Threads are in the sky.

I read a half

dozen or so Pern novels when I was a young teenager. I remember Dragonsdawn and one about a Harper (but

I don't think it was the Harper Hall trilogy). One of them was The Dolphins of Pern. I can't say I

remember too much about them. I remember that the dolphins were very smart, I remember

that the beginning of man's colonization of Pern had a strong science fiction

edge to it but that most of the books taking place later in its history were essentially

fantasy novels. There was one story that featured spaceships and smuggling but

I can't seem to remember the name. Anyway, I've always wanted to start reading

Anne McCaffrey famous Pern series from the start. Not the start

chronologically, I already undertook that when I was younger and I think that’s

one of the reasons I stopped. Approaching the series that way didn’t really

seem to work for more than two books. I’ve since learned that the best way to

read a multi-part series is to do so by order of publication which is what McCaffrey has often suggested readers do (though I completely disregarded

this self-imposed rule with The Wheel of

Time). Still, I’m adamant to stick to it with the Pern novels because I

always enjoyed them but I've always been confused about the internal history

and chronology of the series, mostly because I picked the books at random after

reading Dragonsdawn.

This time around

I decided to read the first book which is a collection of three novellas which

surprised me a bit because the book works pretty well as a whole. I really

liked Dragonflight but I can’t help

but feel disappointed because there are some serious things that simply do not

work. I’ve essentially rediscovered Pern with this book. I remember very little

from the books I’ve read before and that’s probably one of the contributing

factors to my disappointment. In short though, I can summarize things quite

simply by saying that Dragonflight

seriously lacks any emotion. Before I get into that, here’s a bit of plot.

Pern has fallen

on hard times. Every two hundred years, a Red Star passes in Pern’s orbit and

in doing so releases an interstellar pest that feeds on most things biological.

The Threads are silvery-grey worms that fall from the Red Star encased in eggs

which break away in Pern’s atmosphere. They fall from the sky in clusters and,

when they land, burrow deep into the Earth where they breed before setting out

to devour all plants and wildlife they can touch. In order to survive the

Pernese, earth men and women who colonized this distant planet, ride

fire-breathing dragons and burn the Thread right out of the sky! Man and dragon

working together to fight a common enemy, in truth, fighting for their very

survival. That’s what makes Pern an enduring series in the science fiction and

fantasy genres.

The Red Star’s

passing happens between such lengthy intervals that the very culture and

tradition of Pernese society has the chance of dissipating and leaving all of Pern

unprepared for the Thread’s next deadly arrival. It’s during the end of one

particularly lengthy absence of the Red Star (four hundred years) that the

story begins. There is but one Weyr (a dragon fortress) functional on Pern and its

men and women are left scrambling to equip themselves for survival amidst

popular belief that Thread and the Red Star are nothing but bedtime stories.

|

The awesome full cover of Dragonflight by Michael Whelan. These gorgeous covers are one of the reasons

I liked Pern as a teen. I'm very sad the bookstore only had the new, ultra-lame cover shown at the top. |

This particular

story sounds great when summarized like this but McCaffrey’s storytelling left

much to be desired. Her storytelling is mechanical and overtly practical. Her

characters face problem after problem and they meet them head on with solution

after solution. There is a lot of discussion and strategizing but it’s too

neatly organized and nearly no mistakes are made which leads to disbelief on

the readers part. Quite honestly, I will believe the fictional world you’ve

created, even if it includes telepathic and teleporting dragons but it’s

impossible for me to believe that in a time of such dire crisis, humanity will

make practically no serious mistakes. Despite that important flaw, McCaffrey

does succeed in creating a palpable sense of dread.

So far I can

live with these mistakes but it’s difficult to pardon the lack of any engaging characters.

McCaffrey doesn’t even provide a single main character the reader can relate to

or root for. I was far more interested in discovering the mysteries of Pern

(how did Pernese of the past fight the Threads?) than I was interested in

knowing what Lessa and F'lar were up to. Their relationship is frightening to

behold. I’m quite surprised that a woman could have written this book because of

the way the female characters are written. Lessa is continuously treated like a

child by F'lar who is like an angry father to her. More disturbing is their

sexual relationship which I'm sure is tinged with violence based on how F'lar

grabs her by the shoulders and shakes her whenever he gets angry with Lessa.

It's weird and it prevents me from getting emotionally invested in the

characters because I don't like them. As if that wasn’t enough, because of the emotional bond riders share

with their dragons, when Lessa and F’lar’s dragons mate the two humans are

taken over by a sense of dragonlust and also have sex. It’s written in a sense

that makes it seem like the magic of their connection to their dragons is what

makes them do it but I can’t help but interpret this as F’lar imposing himself sexually

on the younger Lessa. I’m not even reading between the lines, I got this

feeling from reading any of their scenes and interactions together. There is no

warmth in their relationship, neither is there any warmth in the relationship of

any of the other characters.

Dragonflight has very little emotion in it and scenes between

Lessa and F'lar are not only an example of this lack of emotion but they make

me feel queasy in their portrayal of a couples. As Weyrleaders of Benden Weyr, these two are Pern's best chance at

survival? It’s not just Lessa and F’lar though, none of the characters really

show emotion. Many of them have drive and ambition and a will to succeed, to survive

but they all do so in a cold and emotionless way.

Gender roles are

also messed up and very uneven. Again, this is surprising because McCaffrey is

a woman, I wouldn’t have expected this of her and my young teenage self either

didn’t pick up on it or I simply don’t remember these elements. In the last fifteen pages, we discover

that what we thought were the old ways, the ways long forgotten, aren’t quite

the ways that F’lar and Lessa have interpreted from their limited sources.

Gender roles aren’t as uneven as they’ve been portrayed thus far in the story

and it give me a bit of hope for the other books in the series. Still, Lessa still

acts like a child in F’lar’s presence, she’s nearly completely dominated. Near

the end of the book she even mentions to other characters that she’s frightened

of F’lar and McCaffrey has F’lar describe Lessa as docile while he’s thinking

about her on many occasions.

The world of Pern:

Where McCaffrey

failed with character and emotionally charged storytelling, she makes up for it

in world building. I’m convinced that it’s because of the fully realized world

of Pern that the Dragonriders of Pern

series has endured.

There are many

things I like about the world of Pern. One of them is that riders have to take

care of their dragons. They have to bathe them, oil their skin, be concerned

about how, what and when they eat. They’re not just awesome fire breathing

lizards with wings; they’re animals that require care and nurturing. Despite

being mostly a fantasy story, McCaffrey approaches many elements that make Pern

in a scientific way. I’ve already mentioned one example in the care of dragons

but she explains other things like how they breathe flame. In a true fantasy

book you do not need to explain or even question this. It’s a basic

characteristic of a dragon. But on the dragons of Pern can only breath fire

when they chew and eat firestones that, combined with the acid in their

stomachs, produces a phosphine gas that ignites when combined with the oxygen

in the air.

While things are

explained in scientific terms, there isn’t a whole lot of technology on Pern.

For all intents and purposes, Pernese live in a world were technology is at the

same level of progression as it was during Europe’s medieval times. This is

particularly interesting (and important to Pern as a series) when considering

how the Holds and Weyrs keep track of their history and traditions. Paper isn’t

a commodity on Pern. Written words are poorly preserved on animal hide and

their history and traditions are mostly kept alive through songs and ballads by Harpers. Similarly to Harpers, weavers are also instructed to make tapestries

for posterity which also serve a dual purpose by covering the stone walls

during the winter months in order to keep out the cold.

I find this

fascinating because the existence of an oral history on Pern makes the battle

for survival something continuous, even when the planet and its inhabitants

aren’t immediately threatened by Threads. Their history is kept alive by Harpers who write songs to educate and entertain all of Pern. Their jobs

is crucial to everyone’s survival, particularly during the two hundred years

where no Threads are seen. They have to make sure tradition and routine

proceedings are maintained to ensure that they will be ready by the next time

the Red Star passes.

For many, many years now McCaffrey has been called the “Queen of Dragons” and

you don’t need to wonder why. With her Dragonriders

of Pern series (which, oddly enough, used to simply be call the Dragon series) McCaffrey has created an

entire world with a culture that revolves around dragons and their abilities

that help them protect their planet from Threads. Everything is structured

based on dragons and their importance to the survival of Pern. What's

interesting is that the threat of Thread occurs regularly but with a

significant amount of time between each occurrence that Pernese tradition and

culture relaxes and changes. Cultural changes aren’t necessarily a bad thing in

our world. Modern life becomes increasingly complex as time passes and change

is inevitable. In the world of Pern however, too much change to tradition can lead

to the destruction of the human colony. The organization of the Weyrs and Holds

was such as to protect mankind.

Harpers are

supposed to be the teachers of tradition by the singing ballads that tell

stories of the past. The problem with this oral tradition is that when three,

four, five or more generations have never lived through one of the Red Star's passes,

these stories and ballads appear to be much more fictitious than they really

are. Tradition must remain rigid and unchanging in order for Pernese to survive

and thrive but the world's technological limitations at recording and teaching

these traditions is so limited that it’s incredibly difficult to maintain a

single way of life. Despite the willingness to maintain tradition that witnessing

the fall of Thread may have on a person, it quickly goes away when the threat

is absent for generations at a time. What I don't understand is how people

refuse to believe the songs and stories about Threads when their main defence

against it, dragons, remains a staple of Pernese wildlife.

Rediscovering

the world of Pern wasn’t what I was expecting. I thought for sure that I would

love Dragonflight from start to

finish. That wasn’t entirely the case since I discovered quite a bit that

disappointed me or simply disturbed me a little. But there was a lot that I

enjoyed that making a return trip to Pern with Dragonquest is a sure thing at this point. I’m optimistic for the second book in the series.

The world has been more or less established and the book is revitalized by the

arrival of several new characters by the book’s end. Along with these new

characters is the promise of more gender balance in the book’s characters as

well as in Pernese society. Although Pern seems to be an exciting fantasy world

in this introductory book to the Dragonriders

of Pern series, it’s a cold, emotionless place. Now that Lessa, F’lar and

all of Pern’s survival is guaranteed, I’m hoping McCaffrey provides a story

that goes beyond that and explores some characters and stories that are less

practical and machine-like in their execution. I need some emotional investment

to go along with the awesome world building.

Much like A Wizard of Earthsea, The Tombs of Atuan is a story about

growing up, about learning right from wrong and the importance of truly knowing

yourself. The twist is that Ursula K. Le Guin tells the story from many

different perspectives. The second book in the Earthsea series tells the story

of Tenar, a young girl who is taken to the Tombs at the age of six to be the

next reincarnation of the One Priestess in service of the Nameless One. The

focus is on her, no characters or places from the first book make an appearance

until nearly the hallway mark. Le Guin restricts our second stay in Earthsea to

the grounds and undergrounds of the Tombs in much the same way Tenar, now known

as Arha, is physically confined on this desert corner of the isle of Atuan.

Much like A Wizard of Earthsea, The Tombs of Atuan is a story about

growing up, about learning right from wrong and the importance of truly knowing

yourself. The twist is that Ursula K. Le Guin tells the story from many

different perspectives. The second book in the Earthsea series tells the story

of Tenar, a young girl who is taken to the Tombs at the age of six to be the

next reincarnation of the One Priestess in service of the Nameless One. The

focus is on her, no characters or places from the first book make an appearance

until nearly the hallway mark. Le Guin restricts our second stay in Earthsea to

the grounds and undergrounds of the Tombs in much the same way Tenar, now known

as Arha, is physically confined on this desert corner of the isle of Atuan. Dave Sim once

said that the essence of storytelling is two people talking in a room. I don’t

recall that ever being presented so beautifully than by Le Guin in The Tombs of Atuan. She harnesses this

idea by having significant portions of the book be Lenar and Ged talking in near

complete darkness in the underground labyrinth. The things they discover about

each other and about themselves by simply conversing were impressive to

witness. A trues tour de force by Le Guin, she’s a master of her craft.

Dave Sim once

said that the essence of storytelling is two people talking in a room. I don’t

recall that ever being presented so beautifully than by Le Guin in The Tombs of Atuan. She harnesses this

idea by having significant portions of the book be Lenar and Ged talking in near

complete darkness in the underground labyrinth. The things they discover about

each other and about themselves by simply conversing were impressive to

witness. A trues tour de force by Le Guin, she’s a master of her craft.