Bumperhead is

the second original graphic novel that creator Gilbert “Beto” Hernandez has

done for Drawn and Quaterly, following last year’s Marble Season. Marble Season

was a semi-autobiographical story that dealt with the joys of childhood. In my review I described it as “love letter to the magical delights and misfortunes

of childhood”. Beto used his own experiences as a framework for the story and

with Bumperhead he set out to do the

same thing with his experiences as an adolescent. The result is a fascinating

story about a young man who was forever shaped by his adolescent years and the

life lessons that can be taken from his past experiences.

Bumperhead is

the second original graphic novel that creator Gilbert “Beto” Hernandez has

done for Drawn and Quaterly, following last year’s Marble Season. Marble Season

was a semi-autobiographical story that dealt with the joys of childhood. In my review I described it as “love letter to the magical delights and misfortunes

of childhood”. Beto used his own experiences as a framework for the story and

with Bumperhead he set out to do the

same thing with his experiences as an adolescent. The result is a fascinating

story about a young man who was forever shaped by his adolescent years and the

life lessons that can be taken from his past experiences.

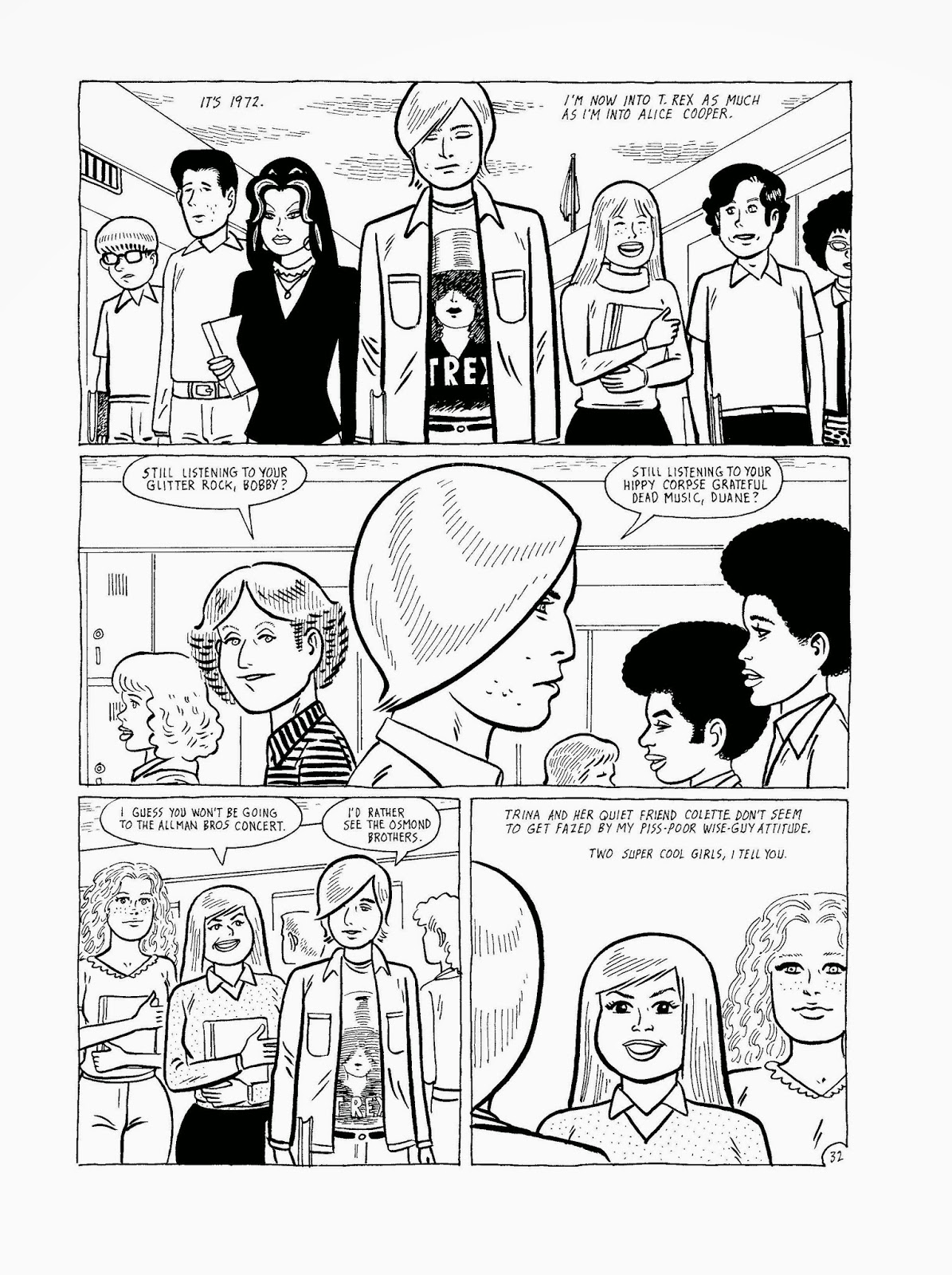

The book feels similar to a few recent works by

Hernandez. Marble Season, of course,

because it focuses on a period in a person’s life and develops that into a

larger narrative. The other comic is the recent collection of Julio’s Day which tells of Julio’s

entire life, from birth to death. Bumperhead

combines these two narrative formats into a familiar yet different story of its

own. The book starts with Bobby, a young man who is teased for having a big

forehead, continues to spend a large portion of the book on his teenage and

young adult years to finally wrap it up with a few pages of Bobby in his golden

years to end with a strange and unconvincing declaration that he’s had a good

life.

Along the way, Hernandez deals with several issues. The

first is the passivity of youth and how that can shape a sad, isolated and

depressing adulthood. Bobby doesn’t seem interesting in committing to anything

one thing in particular. He loves music, he loves girls, he likes hanging out

with his friend and taking part in recreational drinking and drug use but he

doesn’t have any ambition. He does all of these things but a particularly

attractive girl or an excellent record are enough to make him change interests.

When discussing his future with a girlfriend, Bobby mentions he doesn’t have

any interests in going to college. He’s simply happy to be done with high

school and he’s ready for whatever will happen next. What he doesn’t understand

is that by choosing not to pursue any in particular nothing worthwhile will

ever cross his path.

It’s not surprise that he ends up working a job he hates

and living alone. That is, until he discovers the punk movement and decides to

get angry. He uses this anger to create a new lifestyle for himself but it’s

hollow. It has no meaning for him. People get angry for all sorts of reasons

and we often try to maintain the anger for extended periods of time. So long

that we often forget what initially caused us to be angry. Bumperhead deals with this

theme and we see Bobby deal with his anger in different ways throughout his

life only to have it end with the recognition that it’s often not worth holding

on to our anger as it’s a self-destructive emotion.

Bumperhead also

proves to be an interesting remuneration as to how the smallest things from our

past (regrets, thoughts, actions, feelings) can and often do haunt us for the

rest of our lives. It’s a neat look at the idea that high school never ends. No

matter what we do to change ourselves, we remain the same. We struggle with our

identity and the identity of others to the point of stressing ourselves out.

The consequences are that it begins to affect our health. We care so much about

what other people think of us that we change and continue trying to change to

no avail.

Bobby makes his way into the punk scene of the 1970s only

to slowly move away from it all. He returns to the scene a few years later but

he doesn’t recognize the movement anymore. He sees other punks, shirtless with

shaven heads and piercings. He admits to himself that he doesn’t belong

anymore. Did he ever truly belong within the punk scene or was it just a way

for him to run away from his past experiences? Just like he moved from one

girlfriend to the next during his high school days, in adult life he moves from

one scene to the other. At one time he’s a lazy, booze sloshing couch potato,

then he becomes a heavy drugs user only to move in and out of the punk scene

for a few years. Along the way he breaks old friendships, makes new ones as he

meets new people only to sever ties with them, makeup with old friends, and

start all over.

At times Bumperhead feels like an anthology story. Beto uses the same characters is somewhat different roles in order to present the reader with alternatives to the lives of Bobby and the supporting cast. In each iteration the characters seem unhappy and it takes them their entire lives to recognize that they should stop pretending to be something they don’t truly want to be and simply be themselves with all their likes and dislikes. Even the characters who were consistent throughout the entire comic (and their life), such as Colette a born-again Christian who becomes a nun, doesn’t seem particularly happy with her life choices.

At times Bumperhead feels like an anthology story. Beto uses the same characters is somewhat different roles in order to present the reader with alternatives to the lives of Bobby and the supporting cast. In each iteration the characters seem unhappy and it takes them their entire lives to recognize that they should stop pretending to be something they don’t truly want to be and simply be themselves with all their likes and dislikes. Even the characters who were consistent throughout the entire comic (and their life), such as Colette a born-again Christian who becomes a nun, doesn’t seem particularly happy with her life choices.

It’s quite nice that Beto doesn’t appear to be judging

any of his characters. Instead, he presents their lives with such ferocious

veracity as to make his themes that much more effective. Similarly to his black

and white illustrations his storytelling presents a stark dichotomy, heartfelt

portrayals of humanity contrasting with some of the worst decisions individuals

can make in a lifetime.

This year Gilbert Hernandez won his very first Eisner

Award for an untitled short story released in Love and Rockets: New Stories #6. He’s been nominated before but

it’s shameful that the Eisner Award has failed to recognize such an important

creator in comics. Gilbert Hernandez has worked with his brothers Jaime (and

sometimes Mario) Hernandez on their ground-breaking and consistently

spectacular comic Love and Rockets

for more than thirty years. As if that accomplishment wasn’t enough, they’ve

used Love and Rockets as well as

their side projects to tell some of the most harrowing and heartfelt set of

stories in any medium since the 1980s. They’re master storyteller, both of

them, and it’s about damn time that Beto gets his Eisner. I wouldn’t consider New Stories #6 his best work but the man definitively needs

to be recognized as being one of the great storytellers of our time. He’s

worthy of your attention and readership and he’s got dozens of books in print,

just waiting for you to dive in and shake you up a little. When people argue

against comics being a trashy medium or being nothing but superhero stories, I

suggest they read something by Los Bros Hernandez. The works of Gilbert

Hernandez act as definitive proof that comics can tell some of the most

powerful stories in print.

No comments:

Post a Comment